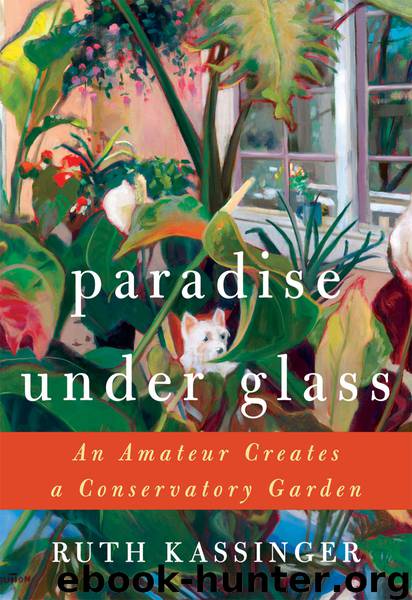

Paradise Under Glass by Ruth Kassinger

Author:Ruth Kassinger

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: HarperCollins

Published: 2010-08-13T16:00:00+00:00

We hung out in the vivarium for a time while I oohed and aahed over the butterflies. I learned that although their lives are sweet, they’re short: usually two to four weeks, depending on the species, the season, and the climate. Monarchs—and monarchs were certainly the species that most appealed to me—that emerge in the spring or summer might survive as long as five weeks. Only those born in the autumn migrate; autumn monarchs live eight or nine months, long enough to journey to their southern habitats and lay eggs.

In the wild, only about two monarch eggs out of a clutch of dozens laid on the underside of a milkweed leaf will survive to adulthood. Because the caterpillars eat only milkweed, which is poisonous, the caterpillars and butterflies also become poisonous, and birds generally avoid them. Disease, however, takes a toll, especially a parasite known as OE (Ophryocystis elektroscirrha). Connie battles constantly to keep OE out of her flocks. She tests any butterfly she acquires by pressing a piece of Scotch tape against its abdomen and examining the tape under the microscope for spores. Butterflies with spores are destroyed. She and her part-time assistant frequently clean all the butterfly cages with a mild bleach solution. She rinses the milkweed leaves with bleach and dips the eggs, as well as newly formed chrysalises. A high concentration of OE will kill a young caterpillar. If the concentration is lower, the caterpillar may go on to pupate, but the butterfly that emerges will be weak or deformed. If it lives, it will pass along OE through its eggs and by spreading spores on leaves. In a population like the one at Flutterby, the pathogen can exterminate all the livestock within a couple of generations. Since monarchs go from egg to butterfly in one month, OE could put Connie out of business very quickly.

The spread of disease, or the potential for spread of disease, is just one reason some wildlife organizations oppose butterfly releases. Farm-raised butterflies, the National Wildlife Federation fears, might introduce nonnative species into new areas, with unknown impacts, or introduce a local disease to a wider population. Even if the species is native to the release area, the farmed population might introduce slightly different genes into the existing population. Could captive monarchs raised in Florida, for example, lack the instinct for migrating to Mexico and, interbreeding, pass on their ignorance?

The Washington (State) Department of Fish and Wildlife also frets about the growing numbers of released butterflies. Not only is it concerned about the thousands of butterflies that newlyweds introduce every year but also about the thousands released by schoolchildren doing science projects. “Releasing non-native animals of any kind teaches a poor lesson,” according to Ann Potter, a WDFW wildlife biologist, “because their effect on the local environment is unpredictable and potentially devastating.” Nonlocal butterflies have the potential to swamp the natives.

The situation sounded worrisome, and I was prepared to think that wedding butterfly releases were less than charming, until I read the literature from the other side.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| African Americans | Civil War |

| Colonial Period | Immigrants |

| Revolution & Founding | State & Local |

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(15320)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14475)

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(12362)

Underground: A Human History of the Worlds Beneath Our Feet by Will Hunt(12080)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12010)

Wiseguy by Nicholas Pileggi(5757)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5421)

Perfect Rhythm by Jae(5390)

American History Stories, Volume III (Yesterday's Classics) by Pratt Mara L(5292)

Paper Towns by Green John(5171)

Pale Blue Dot by Carl Sagan(4990)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4944)

The Mayflower and the Pilgrims' New World by Nathaniel Philbrick(4482)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4477)

Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI by David Grann(4431)

The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen(4381)

Too Much and Not the Mood by Durga Chew-Bose(4324)

The Borden Murders by Sarah Miller(4302)

Sticky Fingers by Joe Hagan(4181)